Mythology 101: When Gods Teach History, Expect Lightning Bolts

A reported 32.4 million people tuned-in to watch the 2024 Paris Olympic opening. The opening ceremony occurred on the Seine River instead of the traditional stadium. An estimated 10,400 athletes from 206 nations were paraded on boats along a 3.7-mile route, passing iconic landmarks for thousands of spectators.

The Olympian stage was set with the Greek god Dionysus, also known as Bacchus to the Romans. Dionysus, adorned with grapes and vegetation, his skin painted in blue, lay on a festive platter, symbolically linking him to his historical attributes of wine, ecstasy, and the madness of any fête.

Screen capture from the opening of the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris. (Screen capture via YouTube, used per Clause 27a of the Copyright Law)

Behind Dionysus, a table of inclusivity emphasizing cultural sensitivity also provided a historical nod to ancient history. At the center, a seated full-bodied goddess, known as Sequana of the Gallo-Roman religion, from whom the River Seine gets its name and the current location of the opening Olympics. The Gaulish tribe that revered her, known as the Sequani, had their sanctuary in a valley in the Châtillon Plateau near Dijon in Burgundy.

Statue of Sequana now housed in the Musée archéologique in Dijon.

“To be offended is a choice we make; it is not a condition inflicted or imposed upon us by someone or something else. It is a habit of rejecting the truth.” – Criss Jami, Killosophy.

The Mirage of social barriers that cloud our eyes

The Olympian gods, in their wisdom, saw through the mirage of social barriers that cloud our eyes, understanding how these illusions obscure our vision of unity and shared humanity. Myth teaches us this lesson through their actions and the symbolism embedded in the performance. By embodying the ideals of community and inclusivity, they demonstrated how social barriers are mere illusions that can be overcome. The banquet scene, with its diverse array of participants, symbolized unity and the breaking down of these barriers. Through their divine presence and the harmonious gathering, the gods illustrated that true strength and progress come from embracing our shared humanity and celebrating our differences. This powerful message was a reminder that the Olympics are not just about competition but also about coming together as one global community.

This misinterpretation of Jolly, of historical art, the Olympic intention, diverted attention away from the true purpose of the games: to promote peace and celebrate diversity and sports. In ancient times, war was suspended, and truces were made to ensure friendly competition and to allow pilgrims and athletes to travel safely.

The Olympian scene in Jan Harmensz van Bijlert’s painting “The Feast of the Gods” illustrates harmony among diverse and, at times, conflicting gods and goddesses in Greco-Roman mythology. The banquet on Mount Olympus celebrates the marriage of Thetis and Peleus, a union.

In the foreground, Bacchus is seen eating grapes while a satyr dances. At the banquet table in the center is Apollo, crowned and holding a lyre; to his far left is Minerva (Athena to the Greeks), wearing her helmet, symbolic of wisdom and war, and Diana wearing a crescent moon. Facing the goddesses is Mars, the god of war dressed in military armor, talking to Venus, the goddess of Love, who accompanies her son, Cupid. Flora, the goddess of spring, is behind them.

Some of the gods featured on the right are Hercules holding his club, Eris is recognizable by the golden apple of discord she brought as revenge for not being invited, and Neptune with his trident.

From Laurel Wreaths to Eiffel Iron: The Evolution of Olympic Prizes

The prizes for victory varied at different competitions. At the Pythian games held in honor of Apollo at the Sanctuary of Delphi in Greece, naked athletes would compete, such as Milos of Croton, who famously wrestled his well-armored opponents bare naked-his prize, likely a laurel wreath. Milos wasn’t the first nude Olympian, as nudity was a part of the first Olympic games held in 776 BCE in Olympia in ancient Greece. In 720 BCE, one runner tossed his loin cloth to finish the race.

At the Olympian games, prizes could include olive leaf wreaths, red woolen ribbons, palm fronds, statues or poems, and a hero’s welcome. For material prizes, besides olive oil and wine, a bronze tripod or shield, maybe even a silver cup. Winners of the Panathenia games, which were held in honor of the patron goddess Athena at the Parthenon, won specially made amphora filled with wine from her vineyards.

The 2024 Olympic gold, silver, and bronze medals feature an image of the Eiffel Tower and the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens. The medals also feature a hexagonal chunk of iron from the original metal used in building the Eiffel Tower.

Apollo Killing the Python by Hendrik Goltzius, published in 1589, is housed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Public Domain

Ancient Greek Gods and Olympian scenes helped people learn to interpret symbols instead of just taking things literally.

- In literature, this means finding deeper meanings through metaphors and allegories.

- In art, it involves understanding the themes and emotions behind the images.

The opening scene of the 2024 Paris Olympics encouraged viewers to see history and the current culture in a theatrical light.

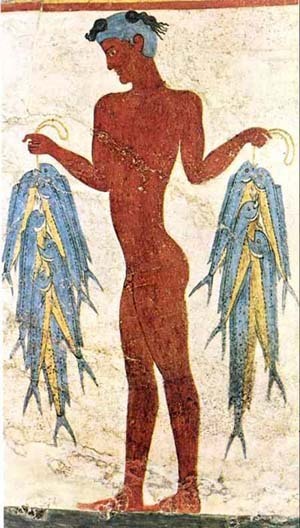

“Man suffers only because he takes seriously what the gods made for fun.” – Alan Watts

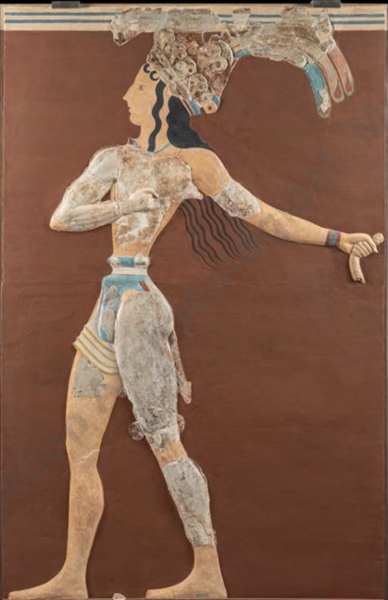

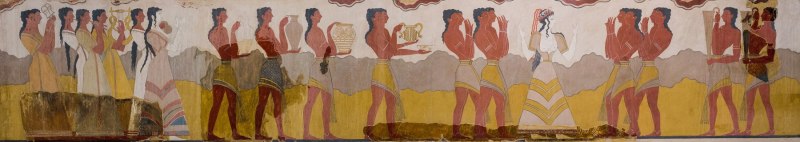

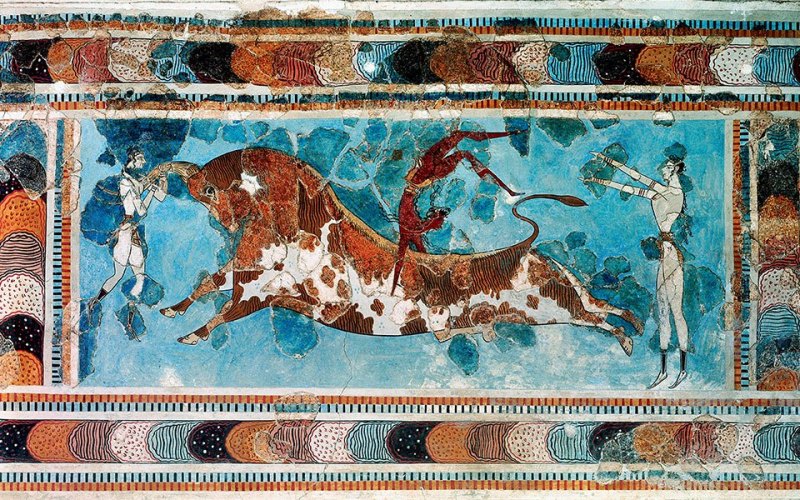

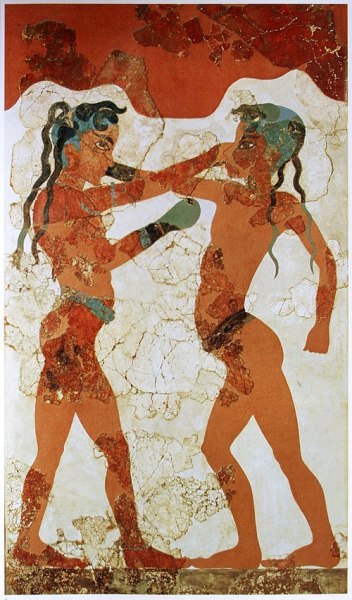

I invite you to review the opening scenes from the 2004 Athens Olympics. Do you recognize the ancient frescoes reimagined from the palace walls of Knossos on Crete or Akrotiri on the island of Santorini (Thera) that showcase Minoan culture and history? As a visual aid, the photographs below are numbered in the sequence shown at the opening ceremony. Notice how Dimitris Papaioannou created these visually stunning and emotionally captivating scenes by easily blending frescos from two temples separated by the Aegean Sea into one. If you had traveled with me on the Starseed Greece Adventure, you would have seen many of these frescoes, walked through the palace of Knossos, and recognized the snake goddess immediately.

The Minoan civilization, which flourished from approximately 2600 to 1100 BCE, is renowned for its advanced art and architecture. The frescoes from Knossos and Akrotiri are some of the most significant examples of Minoan art, depicting vibrant scenes of nature, religious rituals, and daily life. The 2004 Athens Olympics opening ceremony paid homage to this rich cultural heritage by incorporating these ancient artworks into a modern artistic interpretation.

Sources:

Belis, A. (2021) The ancient Olympics and other athletic games, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/articles/2021/7/ancient-greek-olympic-games (Accessed: 29 July 2024).

Chrysopoulos, P. (2024) Coroebus: The first ever Olympic games winner from 776 BC, GreekReporter.com. Available at: https://greekreporter.com/2024/07/29/coroebus-first-ever-olympic-games-winner/ (Accessed: 29 July 2024).

Kokkinidis, T. (2024) Theagenes: The Olympic boxer who became a legend of ancient sports, GreekReporter.com. Available at: https://greekreporter.com/2024/07/30/theagenes-olympic-athlete-legend-ancient-sports/ (Accessed: 30 July 2024).

Provost, A. (2023) Fire ceremonies, Sacred Sites, & Transformation, Thea’s Heart. Available at: https://theasheart.com/fire-ceremonies-purchase-the-replay/ (Accessed: 29 July 2024). Citing Panathenia Day, Athena.

©Thea’s Heart® LLC, 2024 – All Rights Reserved

$39.00