Deliberate Creators

A review of Egyptian temples at Abydos, the Osireion Flower of Life symbols, consecrated water, and reincarnation.

Join us on a Starseed Egypt Adventure, September 6-17, 2024. 12 days, 11 nights.

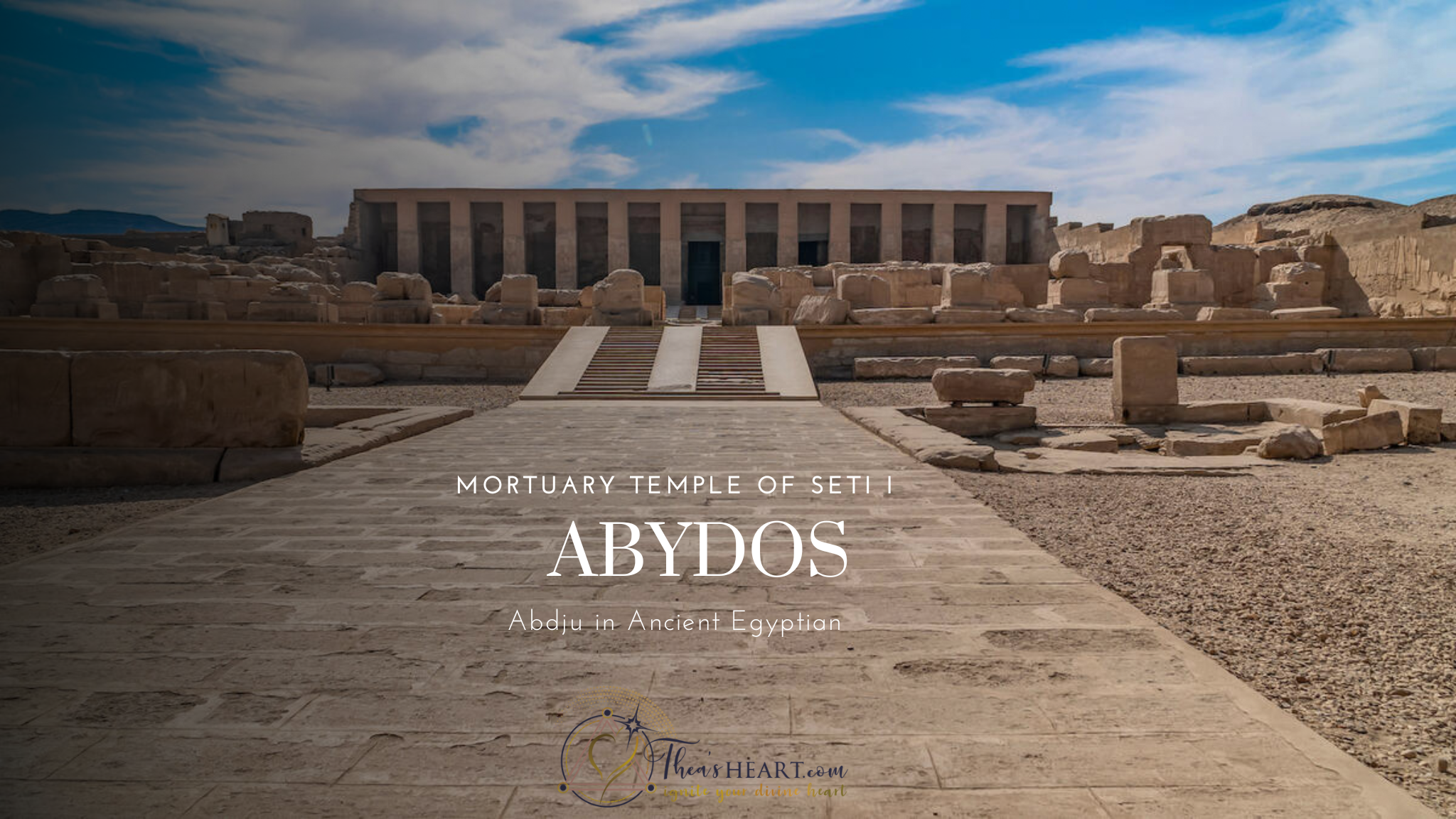

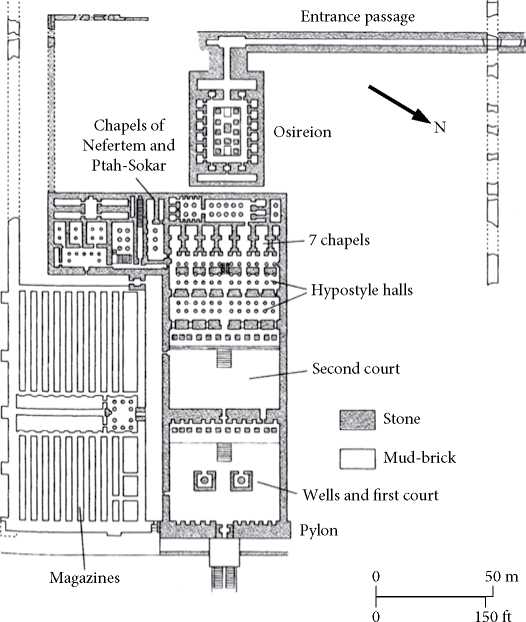

Temple of Seti I & Rameses II

Photo Source: Drawn by Philip Winton. Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. 2000, p. 147.

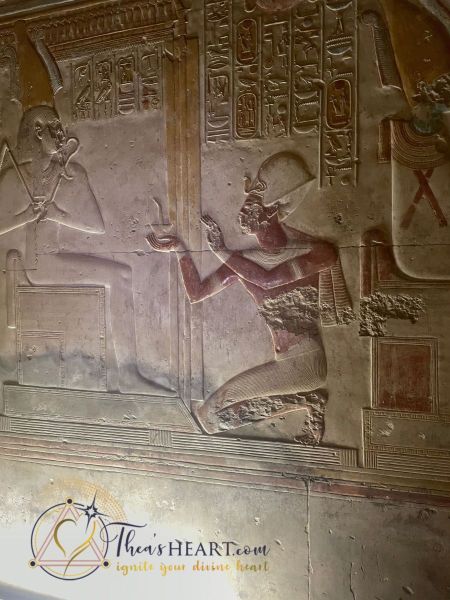

Golden & Godlike

Gold skin and blue hair were associated with the gods, this mummy mask was intended to make the dead person godlike to help him/her reach the afterlife. On top, a winged scarab beetle rolling the sun symbolized rebirth at dawn. Lien, plaster, gold. Abydos, Egypt, c. 200-30 BC. Photo credit: ©Althea Provost, 2022 – All Rights Reserved.

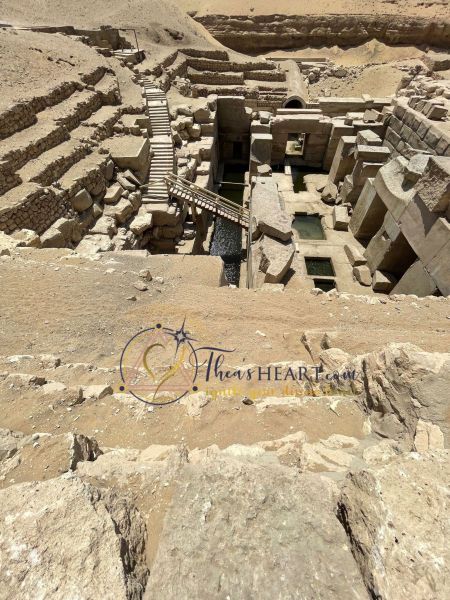

The Osireion

Looking west onto the Osireion Temple at Abydos. Photo credit: ©Althea Provost, 2022 – All Rights Reserved.

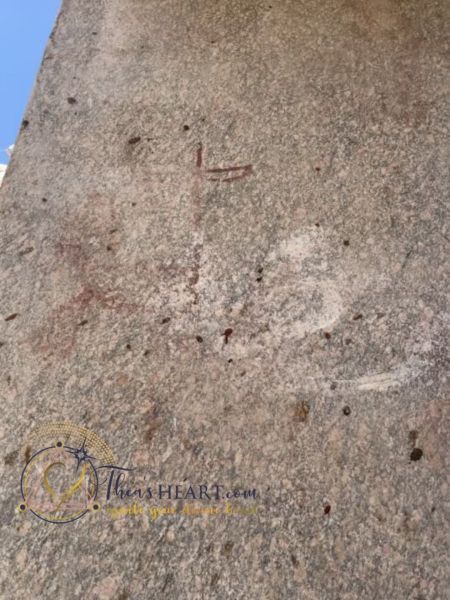

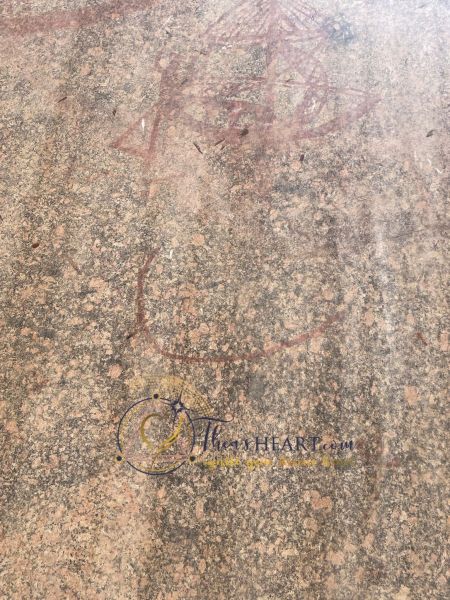

The Osireion, Flower of Life

The megalithic proportion rose-colored granite column depicts several versions of the flower of life symbol. Found within the courtyard of the Osireion Temple at Abydos.

Photo credit: ©Althea Provost, 2022 – All Rights Reserved.

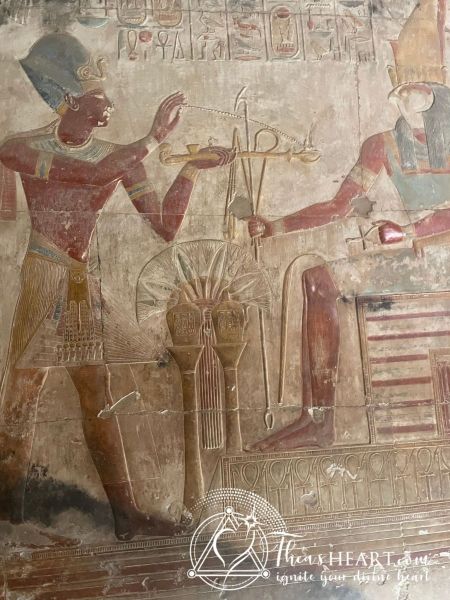

Pharaoh Seti I at Abydos

My impression of the mortuary temple built by Seti I at Abydos was one of exactness. The mortuary temple served a specific purpose, a strict reminder with a clear intention: through daily rituals, a Horus king would transform into a resurrected Osiris, an immortal god.

From ancient times, Abydos was the burial place for Egypt’s earliest rulers. The historic “it” place, Abydos, is one of the oldest cities in ancient Egypt, where legends are buried. Even if some pharaohs are not physically buried there, a symbolic mortuary temple known as a cenotaph will memorialize their legacy. Seti I, considered the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, began in 1279 BCE to build his mortuary temple at Abydos with careful precision, shaping his future destiny in limestone, sandstone, and white alabaster. Deliberate actions, ritually guaranteed, assured his followers of his rightful place even if his body was elsewhere. The Valley of Kings houses Seti’s tomb, the longest and deepest, known now as KV17, which was discovered in 1817. So we have a mortuary building, a tomb, but no mummy. His mummy was found at Deir el-Bahri and is now displayed at the newly built Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza.

Egyptian temples, like Seti’s temple at Abydos, are constructed over generations. Building temples can take up to 150 years to finish. A legacy of family rule underscores the conceptual belief held within the family to think in terms of longevity, eternal existence, and perpetual rule. In theory, to sustain the immortal life of the ruler king-turned-god, priests performed daily rituals within his temple. The temple continues to exist with the blessings of RA, family devotion coupled with devout followers, a continual income stream and military might if needed. Remember, back in the golden days of Zep Tepi, long before Seti, rulers were said to live for thousands of years. When Seti I died unexpectedly before or around 40, his son Ramesses II completed his father’s mortuary temple. In 1213 BCE, when Seti’s grandson, Merneptah, ascended to the throne, he was charged with decorating the Osireion at Abydos. Let’s not forget about Seti’s father, Ramesses I, the founder of the Nineteenth dynasty, whose mortuary temple is also at Abydos. A legacy of mortuary temples becomes a family affair unless you’re considered the black sheep of the family line. The famous King’s List at Abydos, also known as the Gallery of Lists, is located along a passageway leading to an adjacent building called the Osireion. Seti I created a series of cartouches containing the names of preferred and legitimate ancestors. Omitted from the King’s list are the rulers Seti might have considered the black sheep of the family: Hatshepsut, Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun, and Ay. No afterlife for them, according to Seti, at least not in his eternal house.

The ancient Egyptians carefully planned their lives long after leaving their mummified mortal body behind but, oddly, demonstrated purposeful acts of forgetfulness–what can’t be seen nor named cannot exist. For a kingdom that unified in 3100 BCE, a faulty crack amongst careful and deliberate creators emerged: rogue pharaohs. Raze a pharaoh’s shrine or topple a mortuary temple to the ground, etch away their hieroglyphic story, recarve their statuary, and bury their legacy deep in the sand. Yet, they resurrect time and time again. One British woman, Dorothy Louise Eady, locally known as Omm Seti, whose past life recall was so acute, she moved (back) to Abydos to eventually assume (ritual) care of Seti’s temple. Her life story demonstrates memory carried over through lifetimes. Eady’s previous life in ancient Egypt resurfaced, fraught with pain and unrequited love. In that life, at the age of twelve, she was a priestess named Benthreshyt serving the temple of Kom el-Sultan near Abydos as a consecrated virgin dedicated to Isis. A few years later, she met and had a love affair with the pharaoh Seti I that resulted in pregnancy. Benthreshyt committed suicide to avoid a tell-all trial with a guaranteed outcome of death. Eady’s memory was dictated to her by Hor Ra, an apparition that appeared at night over twelve months. She wrote seventy pages in hieroglyphic form depicting this story. In late adulthood, Eady returned to Abydos to formally care for the temple of Seti I. Living a modest rural life with influential power, at the age of 77, she passed away in Abydos on April 21, 1981.

The Osireion | Osirion

The ancient Egyptian priesthood and pharaonic order practiced a religion that studied death and the journey into the underworld. Writing meticulous books such as The Book of Gates and Amduat featured at the Osireon detailing aspects of the soul’s journey. Nothing was left to chance. Unlike the mortuary temple of Seti I, the true purpose and how the Osireion was utilized remains unsolved. Today, we can describe the available layout, drill down to its earlier limestone foundations, test its waters, and not fully understand what makes this water sacred nor account for the mysteries that unfolded within its walls.

The modern appearance of the Osireion is built deep within the ground, with megalithic construction likely built during the reign of Seti I. A significant portion of the rectangular-shaped central hall is void of details. On one rose-granite column are geometric symbols known as the flower of life stained in red ochre (see my photos). Several versions of the flower of life ranging in size, complexity, and degrees of completion can be found in the upper column, as pictured. Perhaps a practice wall?

Contrary to popular belief, the flower of life symbol is not etched by extraterrestrials or a laser-like device. In the Hall of Barques room within Seti I mortuary temple, through careful analysis of the bas-relief, researchers have shown nine stages taken by the painters to achieve the final, precise look. Looking closely at the flower of life symbols, you can see various versions and the column showing several water stains from previous flooding. Between floods and future analysis, we will likely discover additional remnants of red ochre, indicating details were washed away over time. Unfortunately, the Osireion is closed to the public, with access at a high cost. The guard quoted $10,000, then reduced to $8,000 as I walked away. A costly price that allows one inside the central hall for a photo opportunity and not access to other rooms that contain further inscriptions, such as The Book of Gates, the Amduat, the cartouche of Seti I, and the ceiling painting of Nut.

What blows my mind is how pharaonic engineers continued to build monumental architecture over natural springs. Who does that? Our ancients did, often and globally. The Osireion was purposefully built over a life-giving spring, likely consecrated, that was tapped, channeled, and carefully adapted to handle a foundation that would be continually exposed to water. At the time of construction, the Nile reached the temple, and a quay formed around Seti’s temple where boats could be docked and a walkway accessed. Underneath the Osireion, the spring flows outward to the foundation of the Temple of Sety I. Academics have spent considerable dollars and collected numerous water samples from the Osireion, local wells, aquifers, and the Nile itself to learn where the Osireion spring originates. Over decades, the concise answer is to be had. The Osireion water is drinkable and has properties of the Nile but also something that isn’t from the surrounding water supplies. Where exactly it originates, no one knows. Omm Seti began each day at the Osireion, where she would ritually bathe in the water and utilize the water, which had a reported silver-like appearance at the time, to heal local villagers.

For me, the mystery of consciousness begins with water itself. How did Isis appear inside the Temple of Philae at Agilkia island? See course, The Goddess & Egyptian Temple. Water appears in this time-space reality as a solid, liquid, or vaporous gas element. In our current state of evolution with neophyte understanding, as a collective, we have yet to truly grasp its elemental power and engage in a direct, conscious relationship with the life-giving properties of water. Our ancient Egyptians understood and held with reverence what gave life. The flower of life is a sacred symbol, perhaps a geometric nod to the eternal spring. The ever-renewing cycle, whether soul or water, when cared for, stewarded, and in harmony with, leads to the continuation of life.

References:

Al-Emam, Ehab & El-Gohary, Mohamed & Hady, Mohammed. (2014). Investigations of mural paintings of Seti I and Ramesses II temples at Abydos- Egypt. Int. Journal of Conservation Science “IJCS “. 5. 421-434.

Baines, J., Jaeschke, R., & Henderson, J. (1989). Techniques of Decoration in the Hall of Barques in the Temple of Sethos I at Abydos. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 75(1), 13–30. “The paintings of Sethos I were executed in 9 main stages, from initial design to the final painting of details. “

Moneim, Ahmed & Parazak, & Fantile, M & Westerman, J. & Isswai, B.. (2011). Isotope date: Implications for the sources(s) of Osireion groundwater, Abydos Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies (EJAES). Volume 1. 61- 72.

Murray, M.A., Milne, J.G. and Crum, W.E. (1904) The Osireion at Abydos. London, England: Bernard Quaritch.

Winlock, H.E. (1921) Bas-reliefs from the Temple of Rameses I at Abydos. Part I. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Temple chambers and purpose, p. 11

Weblinks:

https://madainproject.com/temple_of_seti_i_(abydos)

https://isida-project.org/egypt_april_2018/seti_en.htm

https://youtu.be/ZrFA-kDHtzg There are various video clips of Omm Seti speaking by several sources and a Wikipedia page. In 2008, Dorothy Eady co-published one book called, Omm Sety’s Living Egypt: Surviving folkways from Pharaonic Times. This book is difficult to find at a reasonable cost. Eady also published two pamphlet-style books on Abydos which can be found through online booksellers.

©Thea’s Heart® LLC, 2023 – All Rights Reserved.